The Battle of Assaye was fought on the 23rd of September, 1803, in western India. This classic Napoleonic-era dust up was a clash between the British East India Company and the Maratha Empire. We’ll skip all the icky colonial horrorshow backstory and go straight to the biffo…

An outnumbered British and Indian force under the command of Major General Arthur Wellesley took on the combined Maratha army of Scindia and the Raja of Berar, commanded by Colonel Anthony Pohlmann, a European veteran. The Maratha Empire had equipped their army European style and hired foreigners to train their troops in modern warfare. Along with 10000+ trained infantry they had 10-20000 irregulars and 30-40000 irregular cavalry. This, in addition to more than 100 artillery pieces with well trained crews, made for an impressive array.

Wellesley’s small force of 9500 troops and 17 cannon was to rendezvous with another British army before engaging. Alas they received faulty intelligence and encountered the entire 50000+ strong Maratha force sooner than anticipated. Afraid the Maratha army would move off to avoid battle, Wellesley opted to attack, despite the disparity in numbers and the strong enemy position on a wedge of land between two rivers.

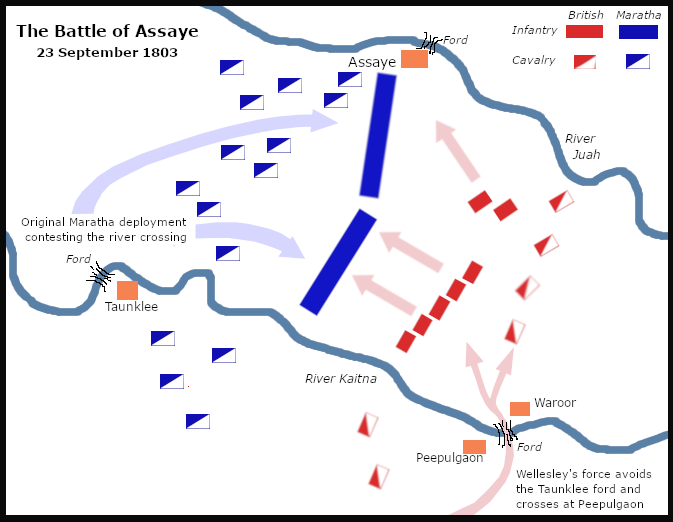

Pohlmann deployed his infantry in line facing southwards behind the steep banks of the Kaitna river with his cannon arrayed directly in front. The masses of light cavalry were kept on his right and Berar’s irregular troops fortified Assaye to the rear. The only apparent crossing point over the river was a small ford directly ahead of the Maratha position.

Recognising a frontal assault was unworkable, Wellesley quickly ordered the river scouted at a likely spot beyond the enemies left flank. It turned out to be fordable and the British army were able to cross unopposed.

Pohlmann saw the danger and quickly repositioned his infantry and artillery. They now stretched from the bank of the Kaitna to the fortified village of Assaye, a mile north on Pohlmann’s new left flank. Wellesley arrayed his small army weighted against the Maratha right flank. He sent two battalions to the north of his line to protect his own right flank.

The British artillery was soon negated by overwhelming fire from the forward placed Maratha guns. Wellesley ordered his troops to advance into the face of the brutal cannonade. The British and Sepoy infantry were heavily pasted by cannister and round-shot but nevertheless overran the Maratha gun line. Despite their losses they promptly advanced with fixed bayonets. The waiting massed Maratha battalions on the southern half of their line fled before the charge of the seemingly unstoppable redcoats hit them.

In the northern part of the field two battalions of Wellesley’s had misinterpreted orders, becoming isolated and under withering fire from the gun line and from the fortified village of Assaye. They fell back and formed square under heavy attack from Pohlmann’s infantry and cavalry. Suffering terrible casualties they were rescued when Colonel Maxwell led a cavalry charge into the attackers, smashing them, then driving on into the northern line which also fled across the Juah river.

Wary of an attack by the throng of cavalry lurking to the west, the British infantry reorganised, allowing Pohlmann’s guns to be re-manned by their surviving crews. The plucky gunners resumed firing on the rear of the enemy infantry forcing Wellesley to re-capture them. During this time Pohlmann rallied the Maratha infantry. They formed up facing south, backs to the river Juah, with their left flank anchored by fortress Assaye.

Maxwell’s cavalry charged again but this time was driven off in a hail of fire, but when the British and Madras infantry attacked, the Maratha troops retreated across the Juah. This prompted the irregulars manning Assaye to flee, followed by the Maratha cavalry. And thus the British won the day. The battle is little known today but at the time it was a surprising victory against overwhelming odds. Arthur Wellesley went on to become the famous Duke of Wellington.

But if this battle could be re-fought, can the Marathas win at Assaye?

Polhmann counters Wellesley’s river crossing appropriately enough, even if the Maratha weight of numbers is curtailed by the constricted field. But will Pohlmann’s infantry actually stick around for a charge? Sheesh, did they even get a volley off when first charged!? If they just ran without even firing then sorry, but they’re crap. And if they did shoot, they shot too soon and/or too high. Which is nothing a bit of flogging won’t fix – train ’em harder! Don’t have enough spare ammo for training? Well then just constantly drum into them “aim for the balls!”

However it wasn’t just the troopers fault. The East India Company had organised mass defections of the eurotrash officers on the eve of battle no doubt contributing to the arse paddling. Heck, I sure as shit wouldn’t stick around if my officers did the bolt! Surely the mercenary officers pay could’ve been made better, or a massive cash incentive offered if the battle is won? Speaking of pay, had the troops been paid recently? Or even given regular rations? Nope. And they ran- well duh!

And the battlefield that constricted the Maratha’s numbers? Pohlmann’s numerical superiority was wasted – he couldn’t bring his overwhelming firepower to bear. Most of the cavalry was trapped behind the massed infantry or on the wrong side of the rivers. Well they chose to fight here! Should’ve fucking scouted for potential fords, hey dipshits. You’d think the locals would know about the one Wellesley discovered. The Marathas could’ve used all that available manpower and checked out the terrain properly. And if they didn’t like the congested field, move off into more open ground. Their army is well drilled enough to do that at least – and they have overwhelming cavalry cover. And if they do want to fight here, then dudes, order the front rank to kneel. Or the rear ranks to reload for the front ranks.

But overall, the Maratha counter moves on the day are excellent. The Maratha commanders can be commended on finding a good spot to fight, wheeling quickly to counter Wellesley’s surprise flanking manoeuvre, and quickly reorganising to the north after the first battle line was broken. If only the infantry had held their ground.

The virtual annihilation of one of Wellesley’s northern battalions showed the Maratha infantry and cavalry could do the job given the right opportunity. Maxwell’s cavalry’s second charge was easily seen off when steady infantry and gunners just stood firm and pulled their fricken triggers!

But speaking of holding your ground, faark me those Maratha gunners had some big brass balls! Taking the first charge, being overrun and decimated, (playing dead when overrun) but then re-manning their guns and recommencing shooting. They again took a charge from infantry and cavalry and fought hard only to be totally exterminated. If only the rest of the Maratha army was as courageous. Notably the gunners had reliable Maratha commanders unlike the infantry.

The Maratha habit of placing artillery in front of infantry did need rectifying:- place the guns between units, on high ground, or in enfilading redoubts etc. The crews were excellent – their placement less so. Sure many European generals of that era (including Wellington) made a forward gunline work, but only with reliable supporting infantry and favourable terrain.

As for the Maratha cavalry, Wellesley’s aggressive deployment in the tongue between the rivers helped negate them. Apart from assisting in the near destruction of a northern British battalion, the entire horde of Maratha cavalry was almost useless. They merely presented a huge existential threat. If the British had been defeated they no doubt would have pursued the survivors mercilessly. But when their own infantry ran from the first British charge they failed to attack the disordered enemy infantry. They also failed to significantly harass the British flanks and rear, let alone envelop the enemy forcing them into square. Perhaps better commanders would’ve helped but I suspect the nature of this mounted force was one of opportunistic banditry rather than clinically professional light cavalry.

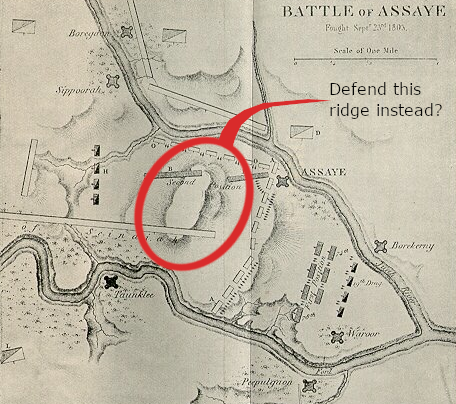

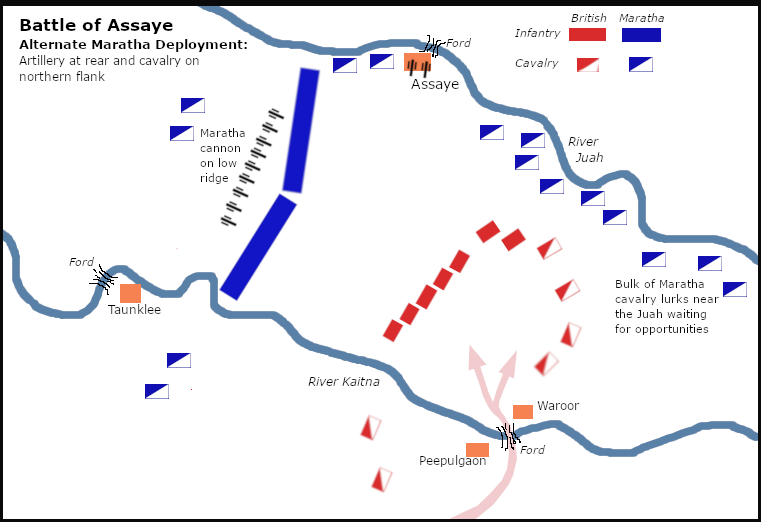

There are a few other ways this battle could’ve been fought that may have changed the outcome. Perhaps, when the British crossed the river beyond Pohlmann’s left, he should’ve redeployed with his artillery massed on the slight ridge half a mile behind his second position and his infantry arrayed beneath it. Assaye would be a quarter mile forward of his left flank but in a perfect enfilading position. This deployment would allow his artillery to fire over, and in conjunction with, the troops. Fingers crossed the Maratha infantry hold steady, enough to start volley fire and annihilate the attackers at range.

Additionally the Maratha cavalry could have been sent to attack the British as they started crossing the Kaitna river. When these cavalrymen are inevitably driven back by volley fire they could form up to the north near the Juah river while the infantry deploys as per usual. Now the British have enemy troops to their west and cav to their north directly threatening their flank. If the cavalry are pressed they may have had to flee across the Juah. Despite the river being in near flood, the horses should be able to cross- the Juah is not the Nile.

But the biggest flaw in Pohlmann’s deployment was in making the original death-trap-river-crossing too bloody obvious. Formed up in plain sight, just waiting behind the main ford! Sheesh. A retarded monkey could see that crossing was suicide! They must’ve thought the British were complete idiots. Be a little cunning about it dudes! The Maratha army moves in formation very well, so use that. Have the entire army loitering about half a mile to the north in apparent disarray. As soon as Wellesley’s main force begins to cross at the “unguarded” ford, march the army at double time to prearranged sites allowing maximum fire onto the river crossing. It will be touch and go timing it right, but with any luck the British will have barely a foothold on the north bank before the lead starts flying thick and fast. Maratha superior numbers and artillery should ensure the British East India Company will be taking a dip in their share prices.

But heck, Pohlmann’s original re-deployment really wasn’t too shabby. If only his infantry had fired an accurate volley and then held their flippin’ ground with fixed bayonets!! The British and Madrassi infantry had already been lashed horribly by cannon shot. A good blast of musketry and the overwhelming numbers of Marathas should’ve sent the foreigners packing.

So could the Marathas win? Well, with the troops and commanders they had on the day, probably not. But if they were to implement a few changes then yes: the Maratha troops needed more drilling in holding their ground and firing correctly; their cavalry needed to be more aggressive; their commanders needed more initiative in arraying their numbers advantage to maximise the firepower including better placement of their excellent artillery; and lastly Maratha paymasters needed to actually feed and pay the troops, and bribe the European sub-commanders harder.

Any one of these factors alone could’ve swung the battle. Fix all these issues and Wellesley would’ve been smashed.

oo000oo

Postscript.

Geez Wellesley was pretty fucking bold. First the escalade at Ahmednuggur then this seemingly impetuous piece of soldiering. Makes you wonder whether he knew all along that the Maratha infantry would run. Did all those deserting European officers tip him off?

As for the forward placed artillery, the Marathas apparently liked their cannons out in front – they gave the infantry confidence (which is a big hint that they wouldn’t stand firm!).

The British East India Company dispatched two armies in an effort to pin down the more mobile Marathas in a pitched battle. The full rivers assisted with this strategy. The Kaitna and the Juah don’t exactly seem huge, even when flooding, especially if you are on horseback, leading armchair legends to wonder why didn’t they just swim their horses over wherever they liked? The mindset back then was probably as follows: a non-swimming Maratha horseman encumbered with weapons, food and what little worldly wealth he has, riding his most valuable possession, will not want to risk losing some, or all of it, through a watery mishap.

Lastly, Anthony Pohlmann seems to have lead a charmed life. Starting as a sergeant with the East India Company, he deserted and took service with the Marathas in 1793. By 1803 he was a Colonel in command of all the Maratha regular battalions at Assaye. He surrendered after the battle and yet re-entered service with the British East India Company in 1804 as a Lieutenant Colonel! Cheeky bugger.